It’s Wednesday afternoon, and someone’s decided to blame video games. It’s easy to get frustrated but, actually, these days are often some of the most fun. Usually what follows is a circus: wagon-circling on Twitter, misinformed headlines in the mainstream press, maybe someone from a trade body going on This Morning to explain how much money video games make, and how many studies there are about them being unanimously good for your kids, your mental health, and your chances of winning the lottery, probably. It is silly, and inconsequential enough for us to quietly enjoy, but it regularly happens, and it usually comes from ignorance.

This time, however, things are a bit different. Someone has blamed video games, less out of red-faced criticism or engagement-baiting rage, and more from sheer desperation. Video games have been blamed by Andrea Agnelli, the chairman of Italian football giant Juventus and, more pertinently, the vice chairman of the catastrophic new Super League that imploded only last night. The context is important, and kind of bizarre.

Travis Scott and Fortnite Present: Astronomical (Full Event Video) Watch on YouTube

If you don’t know football, the big point of controversy is that, as things stand, currently football is quite egalitarian. A new team, or a tiny minnow, can theoretically work their way up from the lowest division in England, say, to the very top of the Champions League that gathers the best teams of Europe, just by winning games. There are huge caveats there – good luck winning that many games without ultra-rich owners, for instance – but fundamentally, in all European competitions, anyone can earn the right to win anything via on-pitch performances alone.

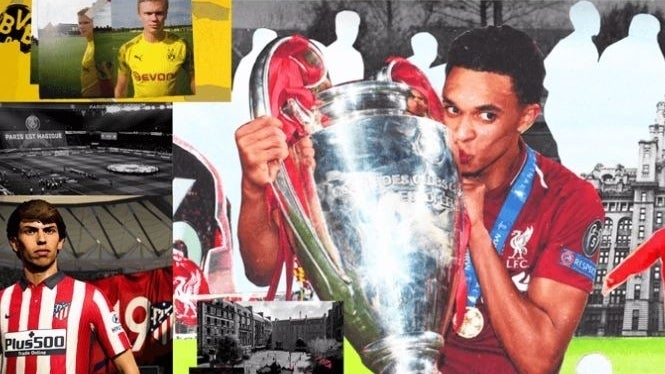

This weekend, however, a group of just the 12 most globally popular, billionaire-owned clubs – minus a couple biggies like Bayern Munich – announced their creation of a “closed” league, where a couple others can join and win promotion or relegation to and from it, but those 12 will always be there, playing each other over and over again in a pointless, dramaless merry-go-round, earning extraordinary sums in guaranteed TV rights money and very loosely promising to trickle that money down to the little guys, honest, while those little guys sweat it out in regular football jeopardy. It did not go down very well. The 12 clubs lost every kind of stakeholder’s support, from local fans who blocked team buses to matches, to players that posted public statements and privately prepared for strikes, to sponsors like Liverpool’s “Official Global Timing Partner”, Tribus, and even such high-integrity parties as Amazon Prime. Ultimately, the plans collapsed less than three days after being announced.